Dieser Beitrag ist auch verfügbar auf:

Deutsch

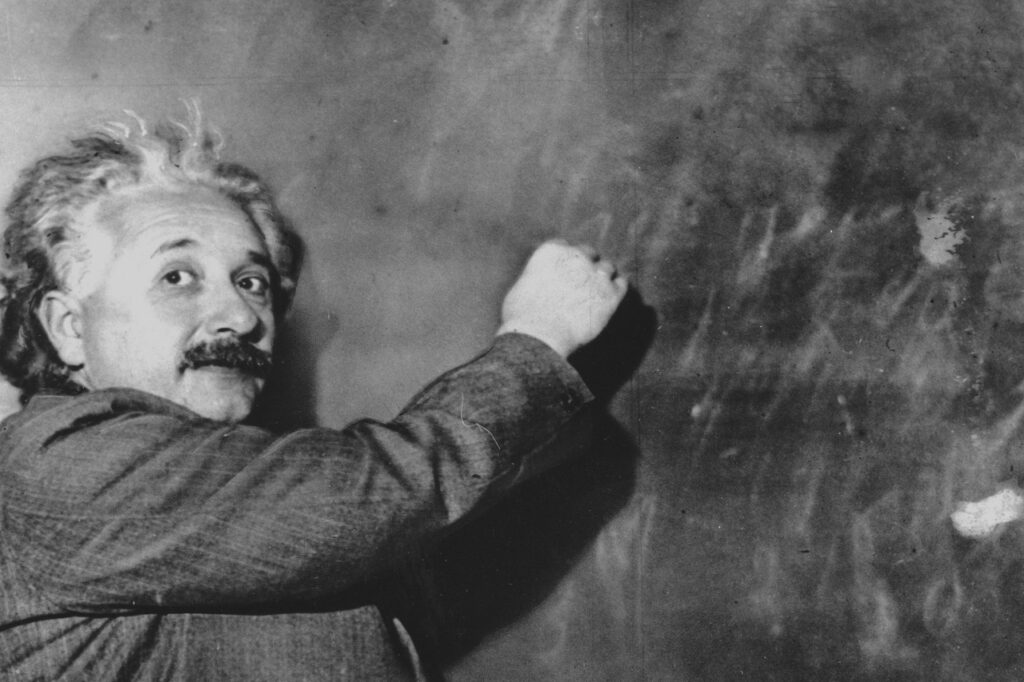

After Albert Einstein died of a ruptured abdominal artery, he was cremated the very next afternoon in Trenton, New Jersey. The ashes were scattered at a secret location along the Delaware River. But not every particle of the great physicist’s body was blown away in the wind.

In the morning of the same day, Einstein’s body was autopsied at the hospital where he had died. After completing the examination of the internal organs, the pathologist, Dr. Thomas Harvey, turned his attention to the brain.

A pathologist stole Einstein’s brain for a secret research project

With a few slices of his scalpel, Harvey removed the most famous brain of the century from Einstein’s skull – and kept it. His goal: to find differences between Einstein’s brain and the brains of other people. Preserved in formaldehyde and cut into more than 1,000 slices, Harvey took the brain with him to each new job in the states of New Jersey, Kansas, Missouri, and finally back to New Jersey.

Sometimes it was stored in its jar in moving boxes, sometimes under beer coolers. The few scientists to whom Harvey entrusted samples in the early years failed to discover anything unusual about the brain.

Rapid progress in brain research

At the end of the 20th century, however, there was an unprecedented surge of interest in brain research. Brain researcher Marian Diamond convinced Harvey that the brain samples would be in good hands with her. In 1983, several pieces of the brain – floating in a mayonnaise jar – finally arrived in the mailroom of Diamond’s university.

When they analyzed the glial and nerve cells in the samples, Diamond and her assistants discovered that Einstein actually had more glial cells per nerve cell than the average person. Glial cells are part of the nervous tissue and therefore of the nervous system. They conduct signals and are involved in metabolic processes and immune defense.

The perfect brain for calculations

However, the difference was only statistically significant in one section of the lower left parietal lobe. This is an area that plays an important role in processing visual stimuli and understanding complex relationships, in addition to arithmetic. Einstein’s brain had 73 percent more glial cells than the brains of the control group of Diamond’s research.

But it was a study published in 1999 that caused the biggest stir. This time, brain researcher Sandra Witelson was given access to something her predecessors didn’t even know existed: Photographs of Einstein’s brain before it was sliced open. Witelson noticed that Einstein’s parietal lobe (in the upper back of the brain) was about 15 percent wider than usual in others.

All in all, Witelson speculated, the structure of Einstein’s brain enabled him to improve neuronal connectivity in areas that were important for visual, spatial and mathematical processing. Einstein’s brain samples are still available for study to this day. However, it is uncertain what scientific value they still have. After decades of storage and several transports across the country, the significance of the brain is probably primarily that it is a reminder of this famous man.